Mayflower

Mayflower is the second episode of the series An Involuntary Trace, curated by This Is Jackalope in Room A in 2021.

This proposal presents David Horvitz and Javier Cruz, who share the ability to communicate complex ideas through exhibits which at first glance appear simple. Addressing the work of both artists is like facing life itself; in its apparent everyday guise, their production puts the viewer in touch with the essence of deep thoughts that are transmitted through gestures of great poetic impact.

Mayflower is a conversation through poetic gestures that materialise in site-specific objects and interventions, seeking to approach philosophical issues like the dimension of space and time, the cycles of life and our perception of the world around us—in a word, our own existence.

In her book The Sea Around Us, marine biologist and conservationist Rachel Carlson (1907-1964) describes how the ancient Greeks saw the ocean like an enormous river that surrounded the world, marking the end of Earth and the beginning of the sky. For ancient geographer Posidonius (c.135-51 BCE), the limitless ocean extended into infinity. In order to record the sound of the Pacific Ocean at the same time in different geographic locations, Horvitz and Cruz arranged to meet on 5 January 2021: Horvitz in Los Angeles (California), in the North Pacific, and Cruz in Concón (Chile), in the South Pacific (in the Mapudungun language, con con means “encounter of waters”). With this attempt at pre-linguistic communication channelled through the ocean, David and Javier propose an immersion into forms of listening that would otherwise be impossible. We find ourselves between two hemispheres, the northern and the southern halves of Earth, tuning in to our own listening experience as a function of the position we occupy in the quadraphonic space, in a state of perception in which the frontiers between the self and the world seem to have vanished.

Mayflower, the title of the show, transmutes into a fragrance that floods the exhibit space and into a narrative of migratory flows—not just of people but also of plants and species that have been transported to other parts of the world, conveyed by oceans that have borne witness to their displacement. Mayflower was the name of the cargo vessel in which the early English pilgrims sailed to the New World, settling in Massachusetts in 1620. The settlers also used the name mayflower for the Epigaea repens, the first plant they saw bloom in spring after their bitter first winter in Massachusetts. Two different varieties of the mayflower plant thus came to be referred to with the same name: the one that made the pilgrim ship famous, also known as haw thorn, which is found throughout Europe, northwest Africa and western Asia, and the wildflower the early English settlers found in North America. David Horvitz’s grandmother, who emigrated to the West Coast of the United States from Japan, has for years kept a mayflower plant in her garden, in this case belonging to the Plumeria species, which is endemic in Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, Florida and Brazil, and is also known as frangipani. A cutting from this plant was brought to Spain a few years ago by curator Alex Alonso Díaz, who took it to his grandmother’s house in Cantabria, where it prospered and grew. The Mayflower essence we encounter in Room A was created from Alex’s grandmother’s description of the flowers’ scent.

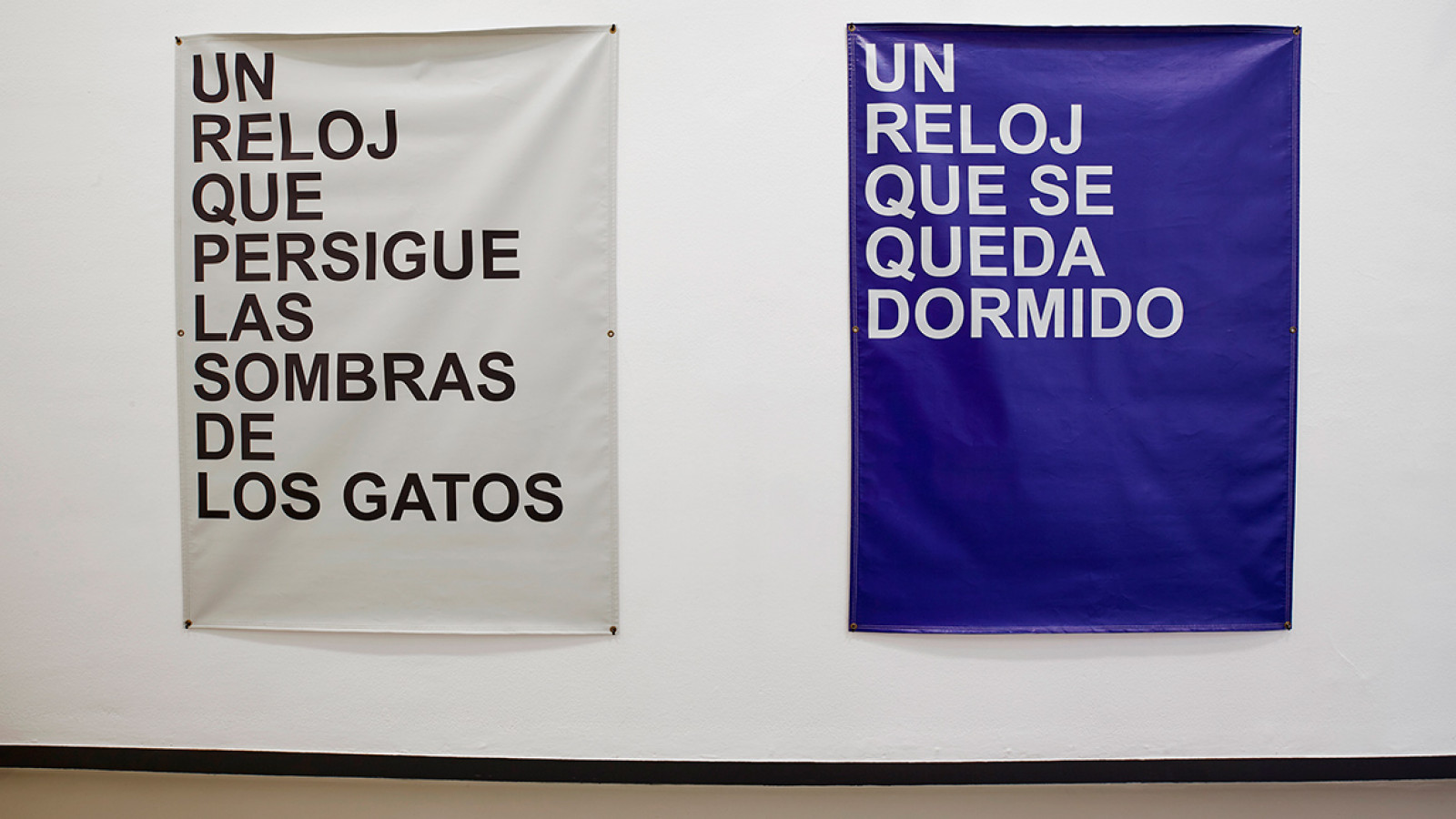

David Horvitz’s clocks and banners are designed to break down the accepted convention of time. They offer alternative forms of synchronisation, such as the minutes that set the duration of a breath, the seconds beaten out by the pulse of a heart, or a clock that simply falls asleep. The perception of time and space has been—and still is—questioned and analysed in a quest for meaning that has given birth to many different theories. Such was the case of theologian and philosopher Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), who distinguished between imaginary time and actual (historical) time. Maimonides (1138-1204), for his part, argued that, in order to exist, time depend ed on motion, while Kant (1724-1804) maintained that time is a necessary representation that underlies all intuition. In her book Telling Is Listening, Ursula K. Le Guin (1929-2018) reminds us that all living beings oscillate, pulse and move rhythmically; we keep time by coordinating millions of oscillating frequencies within our body and between ourselves and our surroundings.

The Sun and the rotation of the Earth also mark the passage of time. It is that transition from day into night that Javier Cruz focuses Sun and Moon, a bath of light that is as beautiful and romantic as it is toxic. Many Madrid evenings display characteristic hues of orange and red resulting from the effect of the waning light as it pierces the nitrous gases of polluted air permeating the atmosphere. Together with chemist Alejandro Gómez Pérez, Javier has been experimenting with nitrates exposed to an exact temperature that causes them to slowly dissolve, in a physical and chemical metaphor for those sunsets that is captured in the glass containers that filter the light in the exhibition space. It is a kind of alchemy that produces a particular time, a landscape, a convention of its own. Hot silver nitrate turns to gas as it floats to the sky and partakes in the sunset, while oxide turns to silver and slopes towards the ground. The resulting experience is like a slice of time, the production of a present continuous that does not belong to the moment in which it happens, as it has two sides: one looking to the past, to its potential, and another that looks towards its future, as waste. A trace.

We enter the space and are tinted orange, becoming one with the sunset—as predicted by Horvitz’s words, Watching you become the sunset, drilled on the wall by Cruz so that the sunlight, which now freely crosses the windows and the wall in Room A, drains through the holes that shape the words. Opposite the lit-up phrase, in another piece by Javier, we find a solidified eclipse of the moon that refers to eye pupils: photo sensitive paper, made of silver halide, develops under the changing light of the lunar eclipse, which cuts out and frames the art its’s pupils, suggesting a subtle choreography of movement as they increase in size while the moon wanes.

The Mayflower exhibit takes us on a journey of the senses through a blown-ups patio-temporal dimension. Gestures and traces attempt to guide us as we drift within a fable of experience, perceiving the world as an organic whole where everything bears relation to everything else: this is the sentiment of the ocean. Landscapes and endless traces of the passage from evening into night, from sunset into the emergence of the moon—and between them, an eclipse.